Bill Barilko and “The Goal”

- Daniel Wyatt

- Apr 15, 2021

- 6 min read

Updated: Apr 18, 2021

Bill Barilko’s story is thrilling, yet sad at the same time. Billy was a small-town boy who made good, only to meet a heartbreaking and sudden end.

Barilko arrived on the Original Six National Hockey League scene at the best of times. Called up from the Pacific Coast League Hollywood Wolves late in the 1946-47 season, he fit right in with owner Conn Smythe’s rough-and-tumble post-war Toronto Maple Leafs. It was beginning of three Stanley Cup championships in a row for Toronto coupled with the youngster making a powerful reputation around the league. Barilko wasn’t exactly the most graceful skater. What he lacked in style, though, he made up for in ruggedness. He took no prisoners. Opposing forwards soon learned to keep their heads up when approaching the Leafs’ zone for fear of “Bashin’ Bill” sending them to “the moon.”

Every so often, the curly-haired blonde liked to march to the tune of a different drummer. He had the habit of pinching too deep into the attacking zone on occasion (and warned about it by his coaches), thus leaving him trapped, unable to get back to his corner position. Off the ice, he was happy-go-lucky, well-liked and a true friend to everybody.

Born and raised in the blue-collar mining town of Timmins, Ontario, Barilko was still only 23 and a veteran of four NHL seasonal wars when he approached the 1950-51 season. By the time he turned 24 on March 25, 1951, the Detroit Red Wings had finished in first place in the regular season (as they did in 1949-50, in addition to a Stanley Cup) with 101 points, while Toronto took the second spot with 95 points.

The semi-finals for the four playoff qualifiers began with the third-place Montreal Canadiens upsetting the high-flying Red Wings of Gordie Howe and Ted Lindsay in six games; and Toronto beating out the fourth-place Boston Bruins, also in six. The stage was set for a classic all-Canadian Montreal-Toronto confrontation to decide who would take home the coveted Stanley Cup in 1951, exactly 70 years ago this spring.

Commencing April 11 in Toronto’s Maple Leaf Gardens, both teams were ready, expecting a close-checking series, with rivalries and mean streaks galore. Leafs’ forward Harry Watson said it best: “We hated the Canadiens, especially Rocket Richard. We were always up for them.” All these years later, many hockey historians feel that the series was the greatest Stanley Cup Final of all-time.

In Game One, Toronto’s Sid Smith scored at the 15-second mark before some people had even found their seats. With less than five minutes to go in the period, Richard intercepted a Barilko pass to linemate Fernie Flaman and banged the puck behind goalie Turk Broda. At 2-2 after regulation time, Barilko saved the day in the first couple minutes of overtime by blocking a hard shot by Rocket Richard, who had an open net with Broda out of position. A few minutes later, Smith scored his second goal to win it 3-2. Three nights later, April 14, Richard scored the OT goal this time for a 3-2 Canadiens win.

Changing venues to Montreal for April 17th and 19th, Toronto won 2-1 and 3-2 as Primeau switched to rookie Al Rollins in net. Teeder Kennedy scored the overtime goal in the third game, and Harry Watson likewise in the fourth game to make it four straight OT games. This set the stage for the fifth game to be held at Maple Leaf Gardens on the 21st in front of 14, 577 fans and three million fans listening to Foster Hewitt’s play-by-play on radios coast to coast.

No goals after one period, Richard opened the scoring at 8:56 of the second by deking Rollins and backhanding the puck over him. Toronto’s Tod Sloan tied it three minutes later and the period ended 1-1. Paul Meger then put Montreal ahead early in the third.

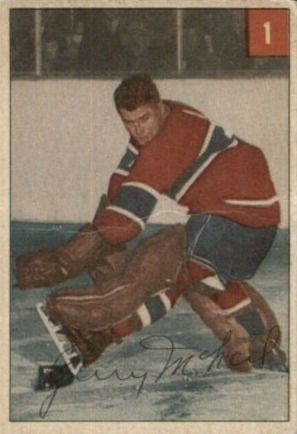

In the Montreal net, Gerry McNeil played brilliantly, stopping 16 shots in the first period including Howie Meeker, Smith, and Barilko--in close twice--in the second period. With just over a minute to play in the game, Toronto pulled Rollins for a sixth attacker, but had to return him to the net when the puck came back to their end. Seconds later, with Rollins out a second time, the Leafs were looking at a faceoff in the Canadiens’ zone with Teeder Kennedy---the best faceoff man in the NHL--squaring off against Billy Reay. Kennedy got the puck and shot it through a maze of legs and bodies…but hit the post. Then with the puck near the crease, Tod Sloan banged in the deflection to tie the game with only 32 seconds on the clock, forcing the fifth straight overtime contest.

Early in the sudden-death overtime, Barilko made another incredible body stop on Richard who had another wide-open net. Then he quickly cleared the puck safely away. A few moments later, Toronto took the play into the other end. There, Meeker had control of the puck, but lost it. As McNeil slipped and fell in his crease, Meeker went behind the net to retrieve the puck and with Tom Johnson checking him closely passed it out front to Watson. The puck went off Butch Bouchard’s skate and ended up in the faceoff circle.

On the left point, Barilko saw his chance, despite his coach always telling him to stay at his position. No one was between him and the goal. Gambling, Barilko raced in, and with a backhanded slapshot fired the puck over the right shoulder of McNeil--still trying to jump to his feet--with such force that he flew through the air and fell to his knees. The fans erupted into thunderous cheering that shook the building as if it was hit by an eatrhquake. The game and the series were all over at 2:53 of overtime.

Harry Watson said later: “It was the perfect ending to a tremendous series.”

Still reeling from his exciting overtime goal, Barilko went home to Timmins in the off-season. In August, he went on what had appeared to be an innocent fishing trip to James Bay with his dentist and friend, Dr. Henry Hudson, who flew his own single-engine aircraft, a Fairchild 24. They left Timmins, but failed to return. Despite an extensive search of the dense northern Ontario forest, neither the two men nor the plane were found. According to a 1962 edition of The Hockey News, the search had covered 100,000 miles, costing $385,000. Both figures set Canadian search records that still stand. My wife and several of her relatives are from Timmins. Her aunt told me a few years ago that Dr. Hudson was her family’s dentist and they knew the Barilko family. According to her, Timmins sank into a deep depression for a long time after the two had gone missing.

The Leafs and their fans were also devastated at the loss. The team dropped to low levels not experienced during their previous decades in the league. The epitome was finishing last in 1957-58. One of the few bright spots was the player called up from the American Hockey League Pittsburgh Hornets to fill Barilko’s vacant defense spot on the roster for the 1951-52 season--Tim Horton. As for the Montreal Canadiens, however, it was the start of 10 straight years of them participating in the Stanley Cup Finals, where they won six championships including five in a row from 1956-1960 to close out the decade.

Then, all of a sudden, 11 years after the disappearance, January 6, 1962, the missing aircraft and bodies of Hudson and Barilko were found by accident in the thick bush, 45 miles north of Cochrane. As if a curse had been lifted off the team, the Toronto Maple Leafs won the Stanley Cup that spring, the first time since Barilko’s famous goal in 1951. On a roll, the Leafs then won two more titles in the next two successive years and a fourth and last one in 1967, the final year of Original Six NHL hockey.

One of the first media people to arrive at the Barilko crash site in 1962 was journalist Peter Worthington from the Toronto Telegram. He noticed that the pontoons of the aircraft had been freshly sliced open with an axe. Apparently, there were rumors at the time that Hudson may have been “high-grading,” the smuggling of gold (used in crowns and fillings) and that the gold could’ve brought the plane down if overloaded. Also, to some people who knew him, Henry Hudson seemed just a little too well off. This is only speculation, of course. The flight and what really happened still remain the bigger mystery.

More recently, the legend of Bill Barilko is celebrated in the 1993 song Fifty Mission Cap by The Tragically Hip. One of the lines refers nicely to THE GOAL: “The last goal he ever scored won the Leafs the cup.”

Yes, it sure did…April 21, 1951, 70 years ago this month.

For further reading on Bill Barilko and his unique life, you have to grab a copy of Kevin Shea’s outstanding book, Barilko Without a Trace (photo below). It’s a page-turner.

Opmerkingen